Brutalist architecture: you either love it or you hate it. But regardless of where you stand on its aesthetic appeal, there’s no denying the cultural and historical importance these concrete behemoths hold. From the imposing buildings of post-war Europe to the strikingly bold designs spotted in cities around the world, Brutalist structures are a significant part of our architectural heritage. Yet, they are under threat.

Today, we dive into the ongoing battle to save Brutalist structures, exploring why it’s an urgent need and what can be done about it.

Understanding Brutalism’s Bold Beauty

Before we can appreciate the urgency of saving Brutalist architecture, let’s take a moment to understand what it is. Born out of the modernist movement, Brutalism is characterized by its use of raw concrete, geometric shapes, and a functional approach. It emerged in the 1950s, peaking in popularity until the mid-1970s.

Despite its name sounding rather barbaric, ‘Brutalist’ is derived from the French term ‘béton brut’ or ‘raw concrete’, highlighting the material predominantly used in these constructions.

Examples That Define the Era

The Barbican Estate in London:

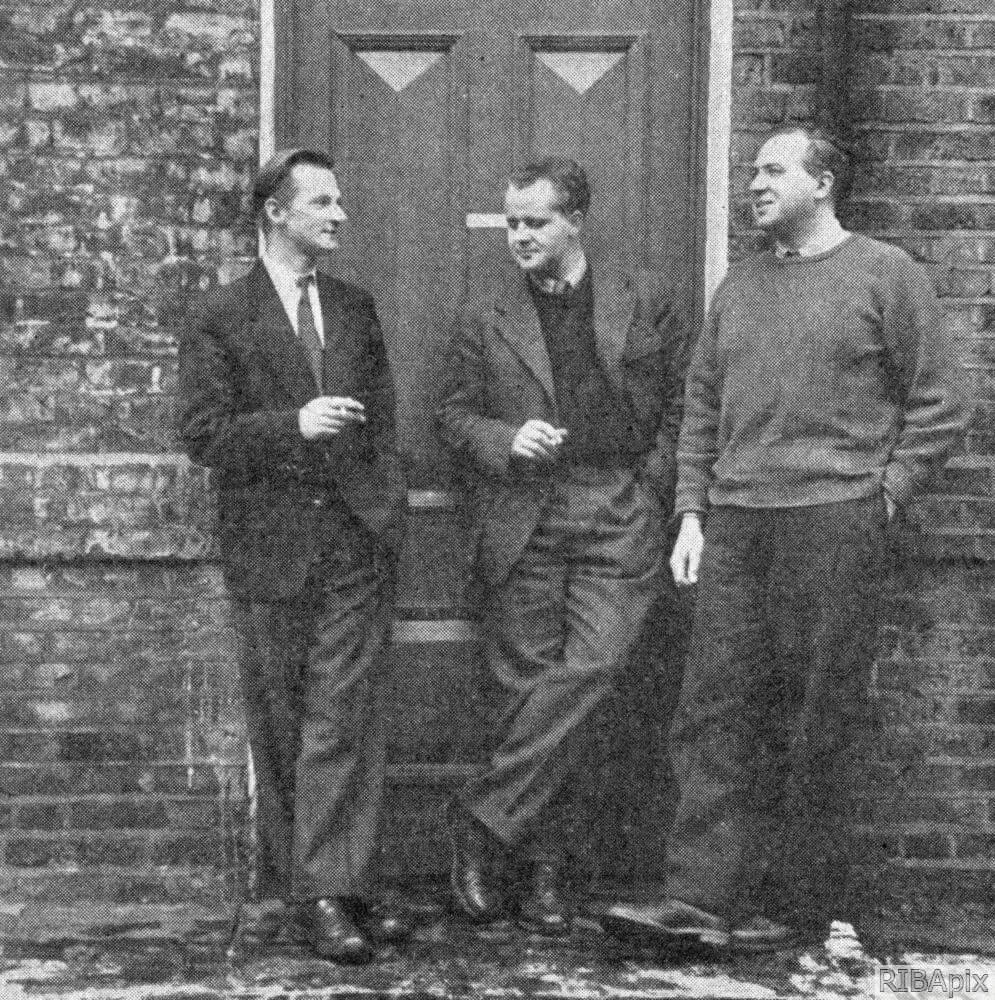

Architects: Geoffry Powell, Christoph Bon, Peter ‘Joe’ Chamberlin . Year : 1953

- This residential complex stands as a testament to the ambitions of Brutalist design, integrating housing with cultural spaces.

The Barbican Estate’s residential buildings comprise 13 seven-story high terrace blocks topped with white barrel-vaulted roofs, and three triangular tower blocks of 43 and 44 stories, with serrated balcony silhouettes. There are also two blocks of townhouses and two mews.

The Barbican Conservatory is the second largest in London after Kew Gardens. It opened in 1984 and is home to two fish ponds with koi, carp, roach and rudd, a terrapin pool, bee hives and over 1,500 species of plants and trees.

CPR’s Barbican design was aimed at, in the architects’ own words, ‘…young professionals, likely to have a taste for Mediterranean holidays, French food and Scandinavian design’. Their ethos was that architecture was for the greater good. It was an optimistic vision for a better society at a time of booming economic growth.

Boston City Hall in the USA:

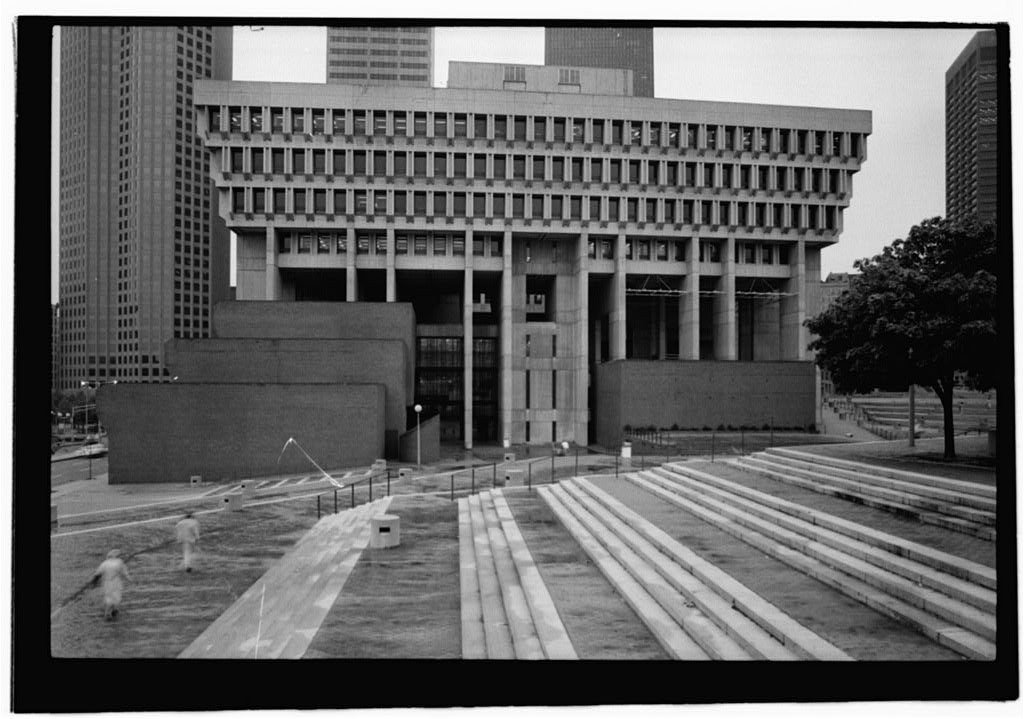

Architects: Kallmann, McKinnell, & Knowles . Year: 1968

Text description provided by the architects. As part of an international competition to design Boston’s City Hall in 1962, three Columbia University professors, Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles, diverted from the typical sleek, glass and steel structures that were being requested by popular demand. Rather than basing their design on material aesthetics, their goal was to accentuate the governmental buildings’ connection to the public realm.

Source: Archdaily

Source: Archdaily

Often a subject of controversy, this building showcases the typical rugged and raw appearance that typifies Brutalism.

The Urgency: Why Save Brutalist Buildings?

The current threat to Brutalist structures mainly comes from misconceptions and economic pressures. Due to their often imposing and “cold” appearance, these buildings can be misunderstood and undervalued. Combined with the expensive maintenance their aging concrete structures often require, many face demolition in favor of more modern, economically viable alternatives. Here’s why this battle is more urgent than you might think:

Cultural and Historical Significance

Brutalist buildings are a snapshot of a pivotal moment in history, reflecting post-war optimism and the role of architecture in societal rebuilding. They represent a philosophical approach to design that prioritizes function, community, and a form of beauty found in raw simplicity.

Environmental Considerations

The environmental impact of demolishing these massive structures is considerable. The energy required to tear down and rebuild, not to mention the waste produced, argues strongly for preservation and adaptive reuse instead.

The Battlefront: Strategies for Preservation

Advocacy and Awareness

One of the primary methods of saving Brutalist buildings is through raising public awareness and appreciation. The more people understand Brutalism’s importance and beauty, the more they are likely to support preservation efforts.

Legal Protection and Regulation

Securing listed status or heritage protection for Brutalist buildings is crucial. This gives them a measure of safety from demolition and encourages creative ways to repurpose these structures while retaining their unique architectural elements.

Adaptive Reuse

Finding new purposes for Brutalist buildings can breathe new life into them. Whether it’s transforming a former government building into apartments or a cultural hub, adaptive reuse not only preserves the architecture but also makes maintenance more economically viable.

Conclusion: A Call to Action

The battle to save Brutalist structures is indeed urgent. As we’ve explored, these buildings are more than just concrete giants looming over our cities. They are markers of our history, representatives of a distinct architectural thought process, and, if given the chance, can be sustainable assets to our urban landscapes.

By understanding their value, advocating for their protection, and thinking creatively about their future use, we can ensure that Brutalist architecture continues to inspire and provoke thought for generations to come. So, next time you walk by one of these concrete marvels, take a moment to appreciate its bold beauty — it might not be there tomorrow unless we act today.

Leave a Reply